Right to Collective Organization

Organizing collectively to defend their interests is one of workers' main Real Rights.

The Importance of Collective Organization

The working relationship between companies and workers is unequal. Companies have economic power and hold the key information about the business. Workers, on the other hand, depend on their jobs to receive their remuneration, which limits their bargaining power.

Since the 19th century, workers around the world have been organizing collectively to amplify their voices and stand up to companies in pursuit of better working conditions.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the UN in 1948, states in Article 23 that "everyone has the right to form and join trade unions for the protection of their interests."

In Brazil, freedom of association is guaranteed by the Federal Constitution, in its Article 8.

The collective organization of workers is a Real Right, as are the eight-hour workday, the right to paid vacation, maternity and paternity leave, protection against arbitrary dismissal, sick pay, accident pay, full reimbursement for the costs of work tools and supplies, retirement, among many others.

Last but not least, unions have been instrumental in the fight against gender and racial discrimination and other forms of oppression in the workplace.

Workers' Platforms and Organizations

The business model of many digital platforms can negatively impact collective organization and workers' demands by incorrectly classifying them as self-employed—even while directing and controlling their activities through algorithmic management—and encouraging competition among them. Platforms can do this through mechanisms such as:

- Establishment of non-transparent criteria for how services are distributed;

- Different pay for workers performing the same service;

- Creation of mechanisms for ranking and punishing workers;

- Control over the number of workers operating on the platforms, which means that they have a large workforce at their disposal without incurring significant costs; and

- Encouraging entrepreneurial discourse that contrasts with the actual reality of workers;

This can create divisions and conflicts among workers, between those who supposedly know how to "work with the app" and those who do not; those who supposedly accept any situation and remuneration and who, in this way, would end up contributing to a deterioration in working conditions.

Workers' forms of organization can be weakened, and consequently their demands too, if they are divided, competing, or in conflict with each other.

“The system adopted by the platform [...] for creating a profile for the delivery person, based on the two parameters of reliability and participation, treats in the same waythose who do not show up for their scheduled shift for trivial reasons and those who do not show up because they are on strike (or because they are sick, have a disability, or are caring for a person with a disability or a sick child, etc.), in practice discriminates against the latter, possibly marginalizing them in relation to the priority group and, therefore, significantly reducing their future opportunities for access to work."

Court of Bologna – Decision on Delivery Platform

Barriers to Collective Organization

In addition to these ways in which the algorithmic management and business model of various digital platforms encourage division, competition, and conflict, there are reports of other more direct forms of intervention in organizations and workers' demands.

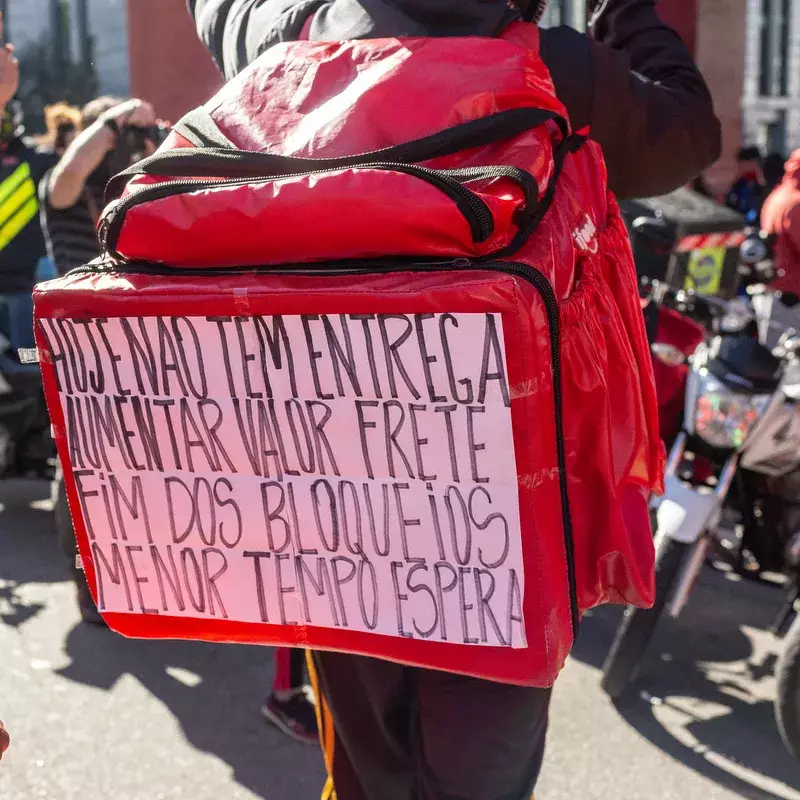

Among them are the blocking of access to platforms for workers who have stopped working in search of better working conditions. Such blockages can occur both through official channels and through so-called "white blockages, " which reduce the transfer of services to them. This may constitute a violation of Article 9 of the Brazilian Federal Constitution, which guarantees the right to strike.

On the other hand, there are widely documented cases of even more incisive attempts by digital platforms to undermine workers' collective organizations, such as:

- Creation of supposed workers' associations that defend interests close to those of the platforms;

- Establishment of laws that restrict collective organization; and

- Hiring specialized companies to organize campaigns against workers' demands, including cases of infiltration among them, defamation, and intimidation of leaders, researchers, and public authorities.

However, this did not prevent the independent organization of the class. To this end, technologies were also used, but in this case, to coordinate workers. Social networks and communication apps were crucial for sharing demands and information and organizing strikes.

Examples of this were the Breque dos Apps (App Strike) in Brazil in 2020 and the coordination of digital platform workers in different countries, which resulted in significant progress in the organization of the working class.

From an institutional perspective, there are also some important initiatives to protect collective organization.

In the legal sphere, for example, it is worth highlighting the pioneering Italian decision in 2020, which pointed out how the automated decisions of a digital delivery platform effectively resulted in anti-union practices, penalizing workers who stopped work to demand better working conditions.

Among legislative initiatives, the European Union's Directive on work on digital platforms established a set of protections for organizations and claims by digital platform workers, including access to information and assessments on algorithmic management.

SOURCES

Marco Gonsales - App strike: the morphologies of the struggle of app delivery workers. In Ricardo Festi – The Tragedy of Sisyphus: work, capital, and their crises in the 21st century, Paco Editorial, 2023.